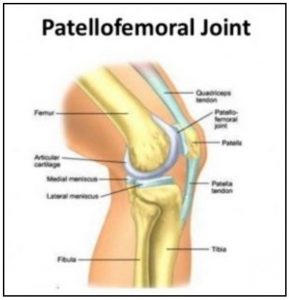

Here are some interesting numbers to consider. On an average 30km ride, the knee flexes and extends somewhere around six THOUSAND times. During low intensity cycling, compressive load through the patellofemoral joint has been shown to be around 1.2X body weight for each pedal stroke. So let’s do the math. Say you weigh 70kg, if we look at this cumulatively your patellofemoral load is around 500 tonnes during a short training ride. To put that into perspective, that’s the equivalent of not 1, not 2, but FIVE blue whales – through each leg! And remember, that’s at a LOW intensity – pretty impressive, right? Let’s go through some more numbers, because you will be glad to hear – running is no better. In a half hour run, we bend and straighten the knee around 4,500 times. While the flexion repetitions are slightly lower, impact is much higher, and compressive load through the knee joint has been demonstrated to be around 5X body weight during landing and load absorption when running. The point I’m trying to make here (albeit in a very longwinded way – sorry) is our knees put up with a lot!

Fortunately, knees are very cleverly designed so that under normal circumstances they are well equipped to deal with these loads. Synovial fluid within the joint and cartilage covering articular surfaces reduces friction and allows for smooth repetitive movement. Bony structure and surrounding soft tissue create a stable moving joint, and the tendons and ligaments in the knee are strong and robust and capable of enduring immense tensile load. However with such high loads and so many moving parts, it is a little bit of a delicate balance, and unfortunately, occasionally things can go wrong. As you can now understand, it’s not surprising that the knee is often the joint which first becomes symptomatic when problems arise.

What Is Patellofemoral Joint Pain?

Patellofemoral Joint Pain (PFJP) is an umbrella term used to describe a condition in which pain is felt around the kneecap. Also known as: runner’s knee, anterior knee pain, or (if you feel like getting medically fancy) chondromalacia patellae, it is characterised by diffuse pain in the region of the patella during joint loading activities. This condition affects 22.7% of the general population – almost a quarter of people will experience this at some stage in their lives, and in what seems a little unfair, it is much more common in the active population. But it gets worse. If you, like me, enjoy cycling here is an unfortunate fact (well, an unfortunate fact in addition to the fact that we have to go out in public wearing lycra) – the prevalence of PFJP in amateur cyclists goes up to 35%. When we consider that outside of fractures, knee conditions account for the most injury time spent off the bike in the professional peloton – PFJP is something you definitely need to be aware of. If you are not a cyclist, don’t tune out. PFJP is also extremely common in runners, and can affect anyone who squats, climbs stairs, or sits with bent knees. Yes, that’s right – sits with bent knees – basically, nobody is off the hook here! What further complicates this condition is that there is a lack of consensus around treatment guidelines. Unfortunately, it is often fairly poorly understood and treated, and studies have shown that at long term follow up (between 5-20 years) it persists in approximately 50% of cases. To add to this already cheerful picture, there is an increased likelihood of osteoporotic fractures in people who have experienced PFJP. Now I’m sure this is all starting to sound rather doom and gloom – but fear not, there IS something that can be done about this. Allow me to continue…

Contributing Factors

It has long been understood that there is a link between weakness in the quadriceps muscles (the large muscle group on the front of the thigh) and PFJP. Exercises focused on quad strengthening have been a mainstay of PFJP rehabilitation and can be an effective way of reducing symptoms and improving function. Interestingly, what the research also shows, is that aside from muscle dysfunction, there appears to be very little consistency in contributing factors. The pain experienced in this condition is usually a result of abnormal loading of the patellofemoral joint. However, the factors attributable to this abnormal loading are varied. Things like: joint kinematics; hip, knee and foot posture; increased or decreased tone in surrounding structures; poor biomechanics; or altered pain pathways all MAY have a role to play, however these factors are not implicated in all cases of PFJP. What this highlights is the importance of an individual assessment to determine which particular factors are relevant to you. A thorough musculoskeletal examination will be able to ascertain what applies to you, and provide a guide upon which your treatment will be based.

If you are a cyclist, you may need to modify your bike fit, your cleat position, or your pedalling style. Saddle height and fore/aft position have a significant impact on knee joint angles (and therefore patellofemoral loading) during the pedal stroke, so these may need particular attention. Your cadence is also important. If you are a runner, perhaps you may need to look at your footwear choices, your stride length or training terrain/routines. What works for one person, will not necessarily work for another and your rehabilitation program needs to be specifically tailored to you if it is going to be effective.

In addition to specialised training programs, there are other adjunctive therapies such as taping, foot orthoses, and knee braces which may be beneficial. However, again, these have NOT been demonstrated to be effective across the board and whether they will work for you depends entirely on your unique clinical presentation. Recipe based treatments are highly unlikely to be successful in dealing with a complex condition like PFJP.

Could the Problem with your Knee be your Bum?

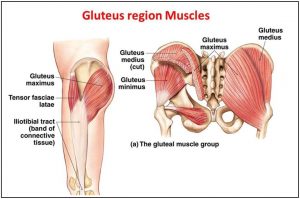

So, it has been established that an individualised rehabilitation program with a quad strengthening component is the best practice for managing PFJP, however, for some time there was still a missing piece to this puzzle. More recently, research has shown that in addition to the thigh muscles, the gluteal muscles (the muscles in your bottom) also have a very important role to play in the prevention and rehabilitation of PFJP. Gluteal muscles of symptomatic individuals were found to be around 20-30% weaker when compared with an equivalent non-symptomatic population. More specifically when looking at gluteal dysfunction, researchers found that the most significant deficits were in the ability of the muscle to rapidly produce force – or the power of the muscle. The glute muscles were not just weak – they also lacked punch. When we consider the important role the glutes have in maintaining lumbopelvic stability, it makes sense that deficits in this muscle group may lead to biomechanical issues further down the chain. With this in mind, your rehabilitation program should definitely incorporate exercises aimed at strengthening the gluteal muscles.

So the moral of the story here is: respect your knees – they put up with a lot! If you want to reduce your chances of ending up with PFJP ensure you maintain good, functional strength not only in the quads, but also in the glutes. And if you do experience knee pain, book in to see your physiotherapist. Remember: if in doubt – get checked out!

Thanks for reading!

Maddy Wright – Physiotherapist